For the past 2 months, I have been studying abroad in Japan attending a private girl’s school in Okayama. From the very beginning, it has been a culture shock. There were a lot of customs and etiquette to learn and adjust to, and 2 months later I am still learning new rules and traditions.

Here are 11 observations and tips to keep in mind if you are studying abroad in a Japanese high school.

1. Prepare for a Long School Day and Know How to Greet Your Japanese Teachers

A Japanese school day is much longer than its American counterpart. In the States, my school begins at 7:25am and ends at 2:00pm, with school activities following. In Japan, school begins at 9:00am and ends at either 4:30pm or 5:30pm (depending on the day).

Japanese students also participate in school activities afterwards, which only adds to the length of their day. In the morning, students have silent reading time which is exactly what it sounds like – sitting quietly at your desk and reading a book. Always remember to clear your desk of all papers, pencil cases, and folders. Your desk should be completely clear.

After silent reading time, students will stand, say “ohayou gozaimasu” to the homeroom teacher, bow, recite the statement on the calendar and sit back down, waiting for their next class to begin. As a Japanese student, you will need to repeat the process of “onegaishimasu” and “arigatou gozaimashita” for every teacher.

Some teachers are stricter than other teachers (for example, my Japanese manners teacher demands our chairs tucked in and a very deep and long bow) while my English teacher only requires us to stand up and say “good morning.”

2. In Japan, the Community Comes Before the Individual

In the US, everyone has their own schedule and moves to their next class when the bell rings. In Japan, it’s different. Teachers come to each classroom to teach their subject. Instead of having a classroom, teachers have their own desk in the teachers’ room (which is usually piled high with papers). Although it is a little unfortunate to not be able to mingle with students from other classes, it gives a student a sense of community and teamwork by belonging to your own class.

While in Japan, I learned that community is much more important than the individual, contrasting to the western value of individuality. Japanese people always seek a collective opinion, and here’s an experiment: try asking a Japanese student about their personal opinion on a topic. You will most likely find them looking around at their classmates, or asking their classmates: “what do we think about this?”

3. Japanese Students are Responsible for Keeping the Classrooms and School Clean

Japanese schools do not have janitors, therefore, students are responsible to clean their classrooms, bathrooms, hallways, and even sweep the courtyard. In my class we are divided into groups and there is a wheel on the wall that is spun every week, allocating each group to a location to clean for that week (or, if you’re lucky your group gets a break).

At the end of the day, after the class bows and says “sayounara” to the teacher, the desks are pulled to the back of the room and cleaning begins (and the whole school becomes very noisy). Cleaning goes by quickly, however, since the entire school is working together and teachers pitch in as well.

I think it is a very good practice for students to clean their school, because it provides a sense of responsibility for your own school and classroom, as well as teamwork/community since we must work together with our classmates to get the task done.

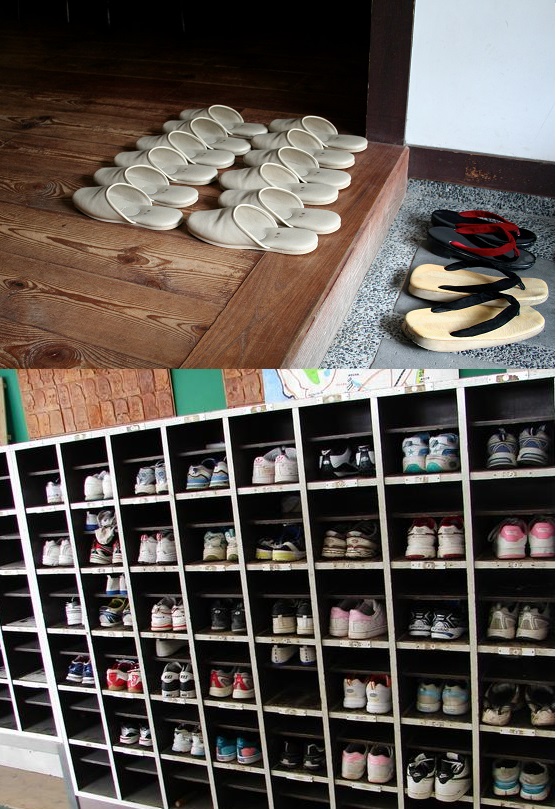

4. Make Sure You Have a Change in Shoes

I’m sure this comes as no surprise that outside shoes are taken off at the front doors, put into personal cubbies, and then school slippers are put on. As a result of this practice, the school stays quite clean, and now I can’t really fathom wearing outdoor shoes into a school anymore – it’s so dirty!

5. Enjoy Your Lunch Breaks with Delicious Japanese Food and Socializing

Unlike American schools where students are divided into lunch waves and go to the cafeteria to eat during that lunch wave, Japanese students eat within their classrooms. Students usually push 3 or 4 desks together and eat together that way, and the lunch blocks are a good chunk of time, so there is time for socializing and fun. However, phones are still not allowed out. At least at my school, I’ve heard differently for other Japanese schools.

The most common lunch is a bento box, which a student’s mom prepares. The contents of the bento vary daily, but they always contain rice, usually some grilled vegetables, shrimp and chicken, and some fruit for dessert. In addition to the bento, mom’s will give their kids a suito , literally meaning “water tower”, which is a water bottle. It will either be filled with water, or rooibos tea.

However, since moms can be very busy (especially with an increasing number of Japanese women entering the workforce), students will buy lunch (onigiri, bread, and salad are popular choices) some days at the konbini (convenience store) or school store. If you are a coffee person, konbinis and school stores sell amazing coffee, and if you are a tea person, you’re in luck – because green tea, rooibos tea, milk tea, any type of tea (and I’m not exaggerating) are everywhere.

6. Understand the Responsibility of Wearing a School Uniform

You are probably well aware of Japanese school uniforms, as almost every school requires their students to wear them in Japan. Each school’s uniform is unique, and it’s fun to look at the variety when using public transport or walking to school.

What most people don’t know is the responsibility of wearing a uniform. By wearing a school uniform, you are representing the school, and carrying the school reputation. Like my school counselor said, “anything you do in that uniform in public, is directly reflected on the school.” To top it off, schools hold their reputations to high standards, and work hard to keep good reputations.

When junior high school students apply to high school, in addition to taking written tests they are assessed on how well they wear their uniform and hair (piercings, an unnatural or even brown hair colour, painted nails or tattoos can prevent a student from getting accepted to a high school). My school has inspections roughly every month, where a teacher will check the length of our nails, the neatness of our hair, our uniform, and overall appearance.

7. Rules are Meant to Be Followed in Japanese High Schools

You will soon notice that Japanese schools, private and public, have a lot of rules. As mentioned before, hair, uniforms, and conduct are all part of the rules. Usually a very important rule concerns phones. It varies from school to school, but for the most part, phones are not allowed. At my school, students are forbidden to use phones anywhere and anytime while on campus. Students are not allowed to walk in the hallways while classes are in session, either. This makes sense, however, because all the classroom doors are see through and it could become a big distraction for students inside the class.

As mentioned before, keeping your desk clear during silent reading time is a rule/expectation as well. There are also standard and self-explanatory rules such as no cheating or being late, but the consequences are much stricter in Japan. If a student is caught cheating on a test, even just once, the school will refuse to write them a letter of recommendation and they won’t be able to go to college!

There are many more rules when it comes to school ceremonies, such as the ceremony held before midterm exams. We must all stand, sit, bow in unison, as well as hold our song books exactly the correct way. Sitting “like a lady” is a big requirement as well, and teachers will definitely let you know if you are not following the rules.

8. Engage in the Culture of Japanese Manners and Ceremonies

At my school I had the opportunity to take a Japanese manners class, which teaches students Japanese tradition and custom, as well as the school’s proud history and traditions. The most prominent aspect of Japanese manners class is the tea ceremony, which we practice every other week in the tea house across campus.

To participate, a student must wear white socks (bought from the school) and have a purchased tea set. The tea ceremony is very complex, and each step and gesture is planned out and calculated. Personally, I always messed up or got confused, but I was fortunate to have very patient teachers and classmates. If you get lost or confused, my tip is to remain engaged and eager to participate.

9. Get Ready to Enjoy Your School Bunkasai

Every Japanese school (and university) has bunkasai, usually occurring around September to October, and they are so much fun! “Bunka” means “culture” in Japanese, so literally, they are cultural festivals. The school is opened up to the public, and usually a large crowd can be expected.

A typical bunkasai consists of both Japanese and American food (corn dogs, shaved ice, etc.), music, karaoke, artwork made by students, and Japanese traditions and ceremonies. Before bunkasai, there is the opening ceremony, which was very shocking for me to witness.

I was extremely impressed with the talent of my classmates, as they danced, sang, played instruments, and performed on stage. I don’t mean to sound harsh here, but I think students at my American high school would need to practice much harder if they wanted to come close to the talent of my Japanese classmates. Students will typically spend weeks preparing for bunkasai, and at my school, each class had a different theme or activity to present in their classroom.

My class chose to make a maze out of cardboard, which was quite a task! We would stay at school until about 8pm each night, so with a 2 hour commute that meant getting home around 10… which was very late, especially with homework to do. However, it was all worth it, because our maze turned out amazing and guests loved it. Once the bunkasai ended, we also had a lot of fun destroying the maze by launching ourselves into the cardboard monstrosity.

10. Long Commutes to School are the Norm in Japan

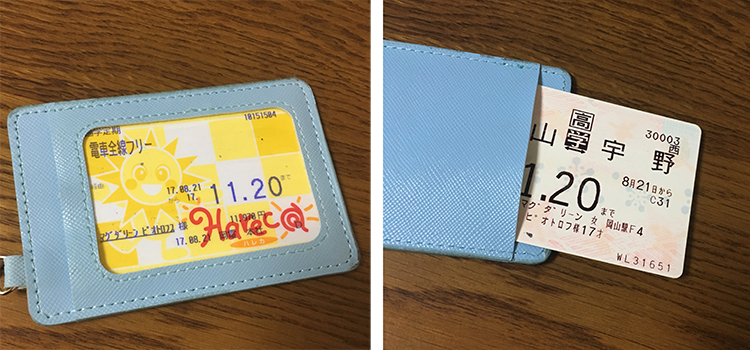

There are four main modes of commute for students in Japan: walking, biking, by train, or dropped off by a parent. Driving oneself to school is not an option, and school buses are non-existent in Japan (at least for high school students). Usually a student’s commute consists of all four of the modes (in my sister and my case) and commutes can be quite lengthy.

A majority of students will either bike, walk, or take the train to the train station and then get on the trolley bus. Trolleys are always packed with students of all ages, from elementary school to high school. The trolley system is really easy to use, as most students usually have an IC card which hangs off their backpacks in a card carrier. When entering the bus, the IC card is placed on the scanner and the commute is paid for.

11. Share Treats and Gifts with Your Classmates and Friends

In Japanese school, friends are, well – very friendly towards each other. For girls, the typical greeting for each other is “yahho!” (very colloquial), and the typical goodbye is “bye bye!” (yes, in English). I found that students like to bring treats (chocolates, cookies, or kibidango) to share with the class quite often, and I think this is a very sweet custom.

As an exchange student, I think it is a good idea to bring treats to class for your classmates. Trust me, you’ll make friends quickly and make your classmates very happy. Speaking of friends, you will find a large variety of personalities in your class.

Just like American students, Japanese students are very different from each other so there are shy students who may never talk to you, excited students who want everything to do with you, curious students who will ask you questions galore. One thing is for certain – you will be the class, or school, novelty. (Expect excited squeals and a lot of selfies on the first day or week).

However, the novelty of you being there will inevitably begin to wear off. So take note of this, and this is important, make as many friends as you can as soon as possible! Because once that novelty begins to fade, students will stop approaching you. While it may feel a little strange and lonely that nobody talks to you 24/7 anymore or you aren’t the class prize possession, it also feels nice to be accepted as just another student. Additionally, it forces you to approach other students, now that everyone isn’t crowding you all the time.

These are just a few of the observations I have made during my time studying abroad in Japan. If you have any suggestions on other tips to include, please add them in the comments below!

Your experience seems awesome. You are so brave to go to a different country. Thank you for making this blog, and sharing it. I like Japan too!

I was wondering, as a exchange student from America, was it hard to make friends because you couldn’t speak their language well?